Blog Layout

The Icebergs

Deron Smith • March 17, 2025

On the last day of spring break, we took the boys to the Dallas Museum of Art. I'm not trying to impress you with our cultural outing—we're just regular folks, and the museum is free.

But I've always loved paintings. They seem to speak. If you listen, you can hear the artist's voice echoing across time. For example, I don't pretend to understand Picasso, but if you ever get the chance to stand in front of one of his paintings, take the time.

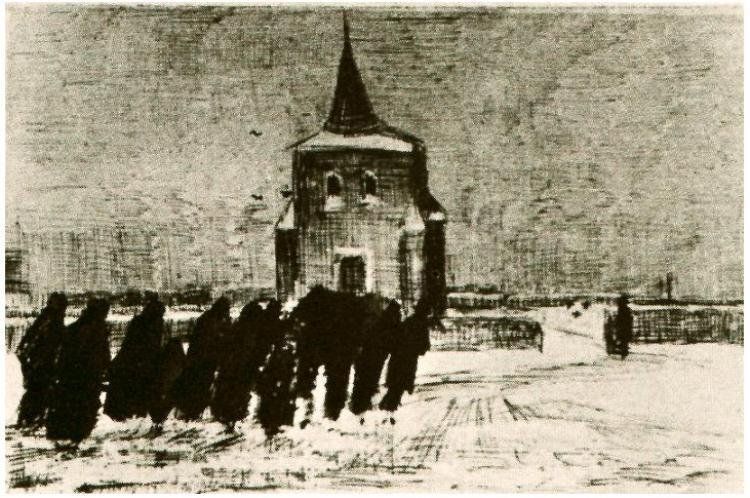

One painting that impressed us was The Icebergs (1861) by Frederic Edwin Church. Inspired by an 1859 Arctic expedition, it captures icebergs bathed in North Atlantic light—an explosion of color frozen in time.

Church was a leader of the Hudson River School, a movement that painted America's landscapes with grandeur and purpose. His work was Manifest Destiny on canvas—patriotic, boundless, and full of promise. By the Civil War, he was a commercial and artistic giant.

When The Icebergs debuted at a fundraiser, it was hailed as the greatest American painting of its time. Even Europeans took notice, which was high praise.

Church sold it to an English railroad baron, Sir William Edward Watkin, who hung it in his Rose Hill estate in Manchester. On a related note, if you own an estate called Rose Hill, you'd better be a baron.

When Watkin died in 1901, Rose Hill became a boys' school. The painting was placed on a forgotten upper landing. At one point, the school donated it to a church, which later returned it because it was in the way.

A masterpiece—once America's pride—had been lost. A historian later said it "more or less sank from sight for three-quarters of a century."

For decades, no one cared about Church or The Icebergs. Then, seventy years later—an entire lifetime—two American art dealers set out to find it. They got close but never quite pinned it down.

Eventually, someone at Rose Hill realized they had a masterpiece and put it up for sale. Manchester's city officials intervened, sending the painting to Sotheby's in New York.

Miraculously, after decades of neglect, it remained pristine, needing only a light cleaning.

In 1979, it sold at auction for $2.5 million—a record for an American painting. The anonymous buyers were oil tycoons Lamar and Norma Hunt. The Hunts donated the painting to the Dallas Museum of Art, where it now hangs.

And there I stood, 164 years after its birth, with my wife and three boys, staring at a masterpiece that had been lost—and then found. If that painting could speak, it would have a story to tell. Like I said—if you listen, you can hear the artist's voice echoing across time.

There's a lot we can learn from this painting. But before we go any further, let's acknowledge that it is a legitimate masterpiece by a great artist. Not everything in life is profound, nor is everything a masterpiece.

That said, there are plenty of lessons in this story. First, fame is fleeting—it's a little like chasing the wind. Second, we often fail to recognize the masterpieces right before us. Third, greatness sometimes needs a light cleaning and a second chance.

But the biggest takeaway is that a masterpiece is a masterpiece because of who painted it, not where it hangs. Sometimes, all it needs is a new gallery.

Share

Tweet

Share

Mail